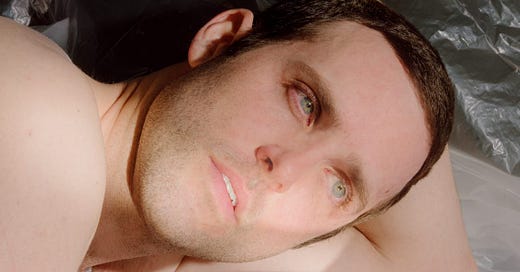

Welcome back! Today I’m super excited to share an illuminating conversation I had with someone who’s been in my music rotation for quite a while: Will Wiesenfeld of Baths and Geotic fame.

Now he’s back with a new release, this time his first album of material for a feature film score. The film is called Big Boys and came out earlier this year. The film is 100% Certified Fresh on Rotten Tomatoes.

I was lucky enough to catch a showing here in NYC. It’s a purely told story of a young boy who starts to have a sexual awakening as he crushes on his older cousin’s boyfriend.

Elevated by Wiesenfeld’s central, ethereal, and vocal heavy score, I really felt some great boundary pushing with the approach that made me super curious to reach out and talk about it with Will in more detail.

I hope you enjoy the convo as much as I did. Topics discussed:

how balancing multiple monikers is more intuitive than you’d think

how scoring Big Boys allowed for a chance to re-approach an older, less well- received Geotic album

how releasing B-sides is humanizing

why it’s useful for musicians and composers to set “ghost-parameters”

how film scoring teaches you nothing has to be perfect the first time

WILL DINOLA: How have you been? What have you been working on today?

WILL WIESENFELD: I'm good. I don't work every day necessarily, but I did have a meeting with my manager and I'm working on some new material.

I have a Baths record that's been finished and we're trying to figure out how to get it out. I may end up self-releasing, which is exciting, but a whole bunch more work.

I have a collaboration song coming out tomorrow that I did with John Tejada, which will be really fun. I'm always in between like a million things.

WD: Yeah. You have a couple of monikers that different [music] comes out on. I'm always curious about how you make those decisions.

WW: I feel like the decision making process for that stuff is not as overt as you might think. It's more just whatever feels like the right thing to do. A lot of it depends on when I'm asked to do stuff. With the film score it was, Hey, can you do this? and I was like oh yeah, sure. I think it times up well with me trying to do these other things.

There are times that I do have to say no to stuff, especially when I'm on a roll with writing my own music. It's annoying to have to say no to things, but I know that if I start diving into doing work for other people right now, I'm gonna lose my momentum. So that's a time when it does kind of become more overt, when I decidedly am not doing this because I have to do my own stuff.

But the differentiation of like Geotic versus Baths versus film scoring, it's not so much a conscious decision. It's just like, what do I feel like inspired to do right now?

WD: So then I guess we can get into this film, Big Boys. Was it mostly a timing thing? How did you and Corey Sherman, who directed it, get in contact?

WW: It was a timing thing, but Corey reached out directly. Corey was a fan and really had an album [of mine] in particular that he was pointing at as reference material. He used [the album] as temp in showing me the movie.

It was a really interesting prospect to me because it was a record of mine that I felt weird about and was also critically weirdly received. It was this record called Sunset Mountain, a Geotic record that was all vocal. When I made that record it was a really fun exercise, but I don't think I executed it well enough. The fact that [Corey] had gotten something out of it, and when he approached me about it, he was like, I hear you for this project with this [record] as a starting point for where we might go. I was very intrigued.

Scoring work in the past, I mean, this is true of all scoring work— the whole concept is that you are not writing for yourself. You are writing for somebody else's vision. And so for me, it's literally compartmentalized into two completely different mindsets, me making music for myself and my own endeavors versus writing for somebody else. Moving into that space typically I'm resigned to making things that aren't necessarily aligned with what I normally do or that I'm not as passionate about, but it was this really cool in-between where a lot of the time I was making exactly what I would want to do for my own efforts, but then applied and with edits coming from a director.

So it was a weird, new thing for me where sometimes I would write a cue and be like oh, I love this. I would totally put this on a Geotic record, but then also get edits from the director about the specifics of how it needs to fit into the scene. And so I would have these fun things where one cue would have versions that were my original version, a version that makes perfect sense for the movie that I ended up liking more, or then a version as a draft for the movie that I ended up liking the best but wasn't the final cut of it.

I feel like the fun of assembling this soundtrack was putting together a greatest hits of the effort of this film score. Cause there were lots and lots of different cues, but I structured it so it's like the whole first half is the film, and then the entire second half are all the outtakes that I was still passionate about that were worthy being on the same playing field as those other songs, but of course didn't make sense contextually within the movie. I totally understand why they weren't in it. It was just that I was still down with them. Even the director, he was like, yeah, these rip. I'm glad you had a place to put them out.

So it's just like a fun effort to show that I had enough music that I felt that way about that came to like 54 minutes in a film that only required about 27 minutes and that I originally composed like two and a half hours worth of music for.

WD: I was interested to hear about the putting together of the soundtrack album, because I do think, I've been trying to get into the composing world more, and I find that, I want to hear more process, through releases [like this]. There's some [score soundtracks] that do include more, but a lot don't— they [usually] include just the material from the film.

WW: On that train of thought, I have that exact sort of thing happening with the Bee and Puppycat soundtrack, another score that I did. The show itself has like a metric fuckton of music and I didn't even realize how much it was until I started putting the soundtrack together. Basically I took every cue that I thought was worth hearing that I still felt passionate about. That became three and a half hours worth of music, over the course of like 16 episodes. Then putting together a digital and vinyl release for it, that had to get whittled down so much, down to about 45 and 50 minutes per volume. So it became Bee & Puppycat Volume 1 and Bee & Puppycat Volume 2, and it's just those two records and those are like the featured soundtrack of the show. But I have three and a half hours worth of music. We could have gone four to five volumes on it, and it still would have had enough stuff.

I think that those two soundtracks are the best of the best, but there are so many other “process tracks,” the fun of which is you never know what is going to be somebody's favorite song. So I'm never against including more things because you never know what's going to hit somebody. A lot of my favorite things from artists are B-sides or things that just don't quite fit the fold of the way the main record flows.

WD: Actually I've been a fan for a while and I think one of my favorite releases were [your] Pop Music / False B-sides records. I think maybe musicians may be the people that tend to like the B-sides type records more than another listener that's not a musician themselves, because a lot of those B-sides are maybe a little more experimental.

WW: Or like in some ways humanizing. It's not necessarily like you're shooting for the best thing in the world. You're just creating. You're just having something come out of you. That's for me what my B-sides process is.

I love hearing that from other artists. You know the band Death Cab for Cutie? I like a lot of their stuff, but my absolute favorite release of theirs is something called The Stability EP, which is three songs, one of them of which is a Bjork cover, and then one of their slowest songs to date, and then an extended, also very slow, very extended version of a song that's like 14 minutes, the Stability song.

It's that kind of thinking that is the thrill of B-side stuff or outtake stuff where it's like, oh, this is still the same group, but they're so faceted and there's more to them and there's more to explore in here.

WD: Totally. I’m curious— I went to see the movie last week. It's playing in New York, which I was super excited by.

WW: Yay! Amazing.

WD: I really liked it. It was a heartwarming movie. And I think with the score, you already mentioned it, but the amount of vocals is really rare for scores. Some horror stuff they use like a kind of choral thing, but I think that melodic kind of stuff with voice— particularly because it's all your voice, right?

WW: Yeah, it is. To be honest, one of the funniest parts about screening it around for audiences is I didn't realize that was a surprise to people. So it was this funny thing of, we were talking about the music in the first or second showings where we did a Q&A. I would talk about the music and be how I recorded it all at home and like use layers of my voice. And somebody would have to double check as a question and be like, wait, all the vocals are you? And I was like, oh yeah it's all my own voice. There would be this oh, in the audience, like this realization. I thought that was super obvious, but it's totally not to people who don't know my music.

Like I had mentioned, [Corey] had said that Sunset Mountain was an influence and he used it as temp music. When we were going into the process of making the score for the movie, Corey was had so many good ideas and was really clear about the tone of the film. How it's shot, how it looks, that it's extremely digestible and comfortable, even though the subject matter itself is kind of thorny and weird at moments, and gets a little abrasive. The whole point is that it's still you never feel like it's antagonistic. It's supposed to feel like you're welcome in the sphere of the movie.

So in order to get to the most essential feel and sound of it, all we were thinking about is Jamie. The whole movie is following Jamie. All of his thoughts, all of his feelings throughout the entire course of what's going. So we were just like, what is that sound?Before I had even come into the thinking of what that was, I feel like Corey basically had the idea that it was the vocals.

I had tried piano stuff. I tried a couple of other things, but we were both kind of like sitting in that realm where it's like, it's probably just going to be me singing. It's probably just going to be a gay person singing a gay person's perspective, in a really gentle, like, I understand you, sort of way.

It was just doing a million passes, seeing what works, seeing what didn't. Having to do takes and cues with my vocals that were, to my mind, very outside of what I normally try to do. There's the sequence where [Jamie] is having a fantasy about seeing Dan right on the campground and the restroom, all that sort of stuff. That had like nine drafts or more until we were getting it right. That's not me shading the director for being particular. It was both of us being like, oh, we're not there yet.

There were a couple of cues like that, where we really had to push to get it out of me, the exact thing that we wanted, but then other queues, like, it was rare, but a couple of them were basically, like, one and done. The whole ending sequence with him and his brother, where they go out to the lake one last time before leaving. All of that was first try.

WD: It definitely works really well. And it's particularly interesting, the fact that the temp was your music. I think my worry with [temp music] is always like, am I copying? Am I defined by it? Which you didn’t have to worry about, in one sense, but then you also don't probably want to repeat yourself.

WW: Yes.

WD: Did [Corey] send you a rough cut or even a final cut before [the] temp [was] in?

WW: I wasn't forced to listen to the temp music in a comparative capacity, it was more just [Corey] like, this is how I sort of feel about it, but you go for it. It wasn't like, oh, I need it to be this, which is usually the service of temp music. A lot of the time [it’s] like, this is the sound I'm going for, please do this.

I think it's very notable that this is Corey's first feature. I personally would have trouble with this if it was my first anything, where I would need to be exercising this level of control over everything. But Corey was not that way with me. He was very open to the collaboration, wanting to appease my own sensibilities with respect to his vision.

WD: Because it's your voice [in the temp], the [score] is going to [sound like you because it’s your voice again]. It's a freeing thing in that.

WW: It made it easier. It wasn't like, Oh, I have to pretend to sound like another person.

One of the funniest differentials between the two is that [on] Sunset Mountain, I had this weird effort in my head to try and sing the entire thing through a closed mouth. So it's humming. I feel like sometimes it works, sometimes it definitely doesn't.

But with this, the big change was like, I don't have to keep my mouth closed! So even just that, I felt that much more liberated going into the process of doing it.

WD: Do you set a lot of rules for yourself, like parameters for each piece that you're working on?

WW: Oh, yeah. I was actually just talking about this with a friend earlier this week, about how musicians or especially musician-composers, especially if you are a solo artist or a producer, you are free to do whatever you want, right? Like philosophically, that's the whole thing, you have the world at your fingertips, you can include any idea that you can think of. So there's a massive amount of choice paralysis with that. Because you can do anything, sometimes it's difficult to even get started or to know where you want to take something.

So the fun incidental practice of establishing these ghost rules for something you're working on helps to guide the process initially. It doesn't mean you absolutely, bottom-line have to stick to them, but it's a great way to get things kicked off. That's what it was with the humming on Sunset Mountain.

A much smaller microcosm of that sort of thing is for a different Geotic record, The Anchorite. Any other Geotic guitar record I've made, the contained phrases keep happening were a set length. They were four to maybe eight bars. The Anchorite was me saying to myself, okay, for this next guitar record, I want these phrases to be much longer, so that when you're hearing the things repeat it doesn't feel so obvious that it's looping.

It feels more like you're listening to a song versus you're listening to a short loop. It's not even that adventurous, but it was an effort that I hadn't applied to that record process before. And it was enough to drive the entire concept of making it.

WD: Is that something where that's a thing in the discovery, where you're working on a piece of music, you don't even know if it's Geotic, Baths, you don't know what it's for, and then you're like, oh, this is interesting if I loop this, you know? And then from there it's turning out cool and now I feel like I could develop some more material off of this idea? Or is it more the other way of, I am thinking I want to do a new Geotic record and what are some ways that could push it into new territory?

WW: It's a bit of both. If I feel like if I'm in the midst of working on something, but I have a tendency to start falling into similar practices or start falling into things that I do often, I have to do a conscious break from that. I have to consciously tell myself to be like, oh my god don't do that again. I have to forcibly break myself out of that habit. So usually the idea of a new set of ghost rules or breaking the mold, that usually happens outside of the recording process and I apply it either to something I'm already working on or do it before I've even started.

In talking about that record with lengthening those loops, I hadn't even sat down to start recording it, yet it was just that concept came to me because I was listening to an older one and I was just like, I wish these were just like a little bit longer.

There are songs that I work on where I have a voice note for an idea that's late at night that I don't do anything with, and I randomly listen to it three weeks later, and I'm like, oh, I need to apply this to something and create something out of this. I don't know why I left it alone for so long. And that steers an entire process where I need the whole rhythm to mirror what I did in this voice note.

WD: Because you have these multiple monikers, you do have to set these parameters also for that, too, so that you don't feel like you repeat yourself.

Because when I was looking at the track listing for Big Boy's score soundtrack, I was like, it's basically a double album in terms of like half the material is from the film and half the material is from the process.

Some musicians might be like, you know what, this stuff that didn't make the cut, maybe I can recycle this or I can save it and hold it. I'm curious if you would talk about why that felt like NOT the choice.

WW: I think for me, it's just fun to exhibit it as part of the process. I feel like there's something that felt incorrect about taking those extra songs somewhere else and using them for something else. It just didn't feel like it made sense to me emotionally to do that.

And so trying to showcase the process of working on this movie as much as possible was way more thrilling. Because some of them are so disparate from others that it's interesting to hear all these different angles of approach on things. I think it helps put in perspective how much goes into trying to get a score together or trying to make a movie work.

WD: I mean, it's one of the reasons I wanted to reach out to you and talk to you about the process, because I did really admire, not just the music itself, but that choice of releasing it and that choice of showing the process.

WW: I really appreciate you reaching out to me, because it's technically the first interview I've done about it. I've talked to people in person in Q&A's, but I haven't really talked much about the score.

Because there's also this thing, which I'm finding out now for the first time, but a score in general doesn't sell anywhere close to the way an album from an actual artist sells. So it's an interesting new world for me. Maybe next time I could have done more PR, but for a first-time go of this sort of thing, I'm really happy with how it turned out.

I'm sure people are going to discover [the score] as they discover more of my discography. The deeper they go into it, they'll be like, oh, shit, you have an entire film score. And then listen to it and be like, oh, this is like a Geotic record, completely on its own outside of the context of anything else. That's kind of my hope with it.

It's probably just going to be me singing. It's probably just going to be a gay person singing a gay person's perspective, in a really gentle, like, I understand you, sort of way.

- Will Wiesenfeld

*Hi again! If you’ve been enjoying this post and want to hear Will’s big takeaways from the scoring process, as well as some of the music, shows, and video games that have been inspiring him lately, that section is for paid subscribers and just a few clicks away.

I want to keep most of this newsletter free and accessible, but I do want to experiment with the subscription model. Five dollars a month or a discounted fifty for the year will get you access to the remainder of the interview and future posts like it, as well as providing me with monetary encouragement for keeping this newsletter going in the new year!*

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to do to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.