Hey guys! Today I’m sharing a wonderful conversation with one of my favorite music trend analysts out there today: Jesse Cannon.

Jesse is a Producer, Marketing Strategist & Mixer/Mastering Engineer. I’ve been following him for a while now, because he’s got tons of great resources for musicians to understand how they might want to promote their own music. I’d point you in the direction of his newsletter Music Marketing Trends and YouTube channel Musformation which I highly recommend. His company Musformation Growth also produces a ton of podcasts and more recently is branching out into video work.

I sat down to have a conversation at a coffee shop in Greenpoint, Brooklyn to pick his brain. For an intimate experience, you can listen to that audio unedited, above. Below is a streamlined, readable version.

Topics discussed:

why album covers are dying

how contradiction is the “conversation”

how emotional alignment in film scoring connects with “the making reels grind”

why your music project should be your “art” project

Jesse’s current Adam Curtis tattoo as well as his planned Aphex Twin tattoo

WD: I don't know if you read any of the other newsletters I’ve done, but [they’re] usually casual and I'm just trying to have more of a conversation than ask you questions. I'm kind of looking for it to go wherever it goes.

As a starting point, I've been noticing a lot of artists omitting their artists' names on their album covers, sometimes not even having the title of the album on it, but Brat obviously has the title on it. Still, no [artist] name.

JC: So in the 90s, I ran a couple different record stores, one on St. Mark's, which was the big punk record store I was the buyer for. There'd be this funny thing that would happen with vinyl. Sometimes they would only have the artist's name on the side of the vinyl. When you buy cheap vinyl, that often crinkled or faded. You have no idea what record it is. You can't even stock it… [So] you had to have the name, you had to have it so people saw it. If you didn't just breeze through it and say, oh, that's this, I've heard of this, you're losing an opportunity for sale.

The other thing is, going from the 40s into the 60s we get this professionalism of music where we start to see best practices. The only people who can afford to do vinyl are not very indie people. For a long time there's these established labels that build best practices and learn this is what we should be doing to optimize sales.

And then we've had, ever since the music business unraveled since 1999 and the music business became the internet music business, is everybody being able to do it, but a lot of people don't know best practices.

So let's say the manager says, you know we should really have the name on the album cover so people can identify it when it's on iTunes. A lot of times the artist goes, who cares? And the fight is over because most of these managers don't know enough to push back. They don't know best practices.

The other thing we start to really see a lot is that, in general, when is the art being presented without the context of what it is? So if you are having that argument with your manager or even your bandmates are pushing back to that, it's like, well, tell me when the art's going to be seen without the context of who we are? If it's on Spotify, it's always right next to which album this is. If it's on these things, sure, the font may be small, but the argument just becomes less and less so that it is necessary to have the artist's name and context in full, especially when it is .001%. Less than .001% of releases make it to a physical format.

WD: What do you feel like best practices should be now?

JC: Well, there's an argument for recognizability of a brand from far away is like one of the most helpful things. I've worked with the Misfits for a lot of years. For 25 years I've worked with them. I had a really interesting thing the other day. I was talking to a teenager, and I'm like, do you know who the Misfits are? [They respond,] I don't know them. I pull up the skull. They're like, oh, that thing? Of course.

They are the first group that on the Coachella Flyer are not in the Coachella font. They actually got their logo in there because John, their manager, is an adamant defender of their brand at all costs and would rather walk away from negotiation than not have their brand reinforced.

So what I would say is when we're talking about best practices and we're talking about what people should do is, yeah, you want to be reinforcing the logo. Like, it's just, like, Alec Baldwin, Glenngary Glenn Ross, “always be closing.”

WD: Yeah.

JC: Always be logo-ing.

WD: Right.

JC: Right now, we're talking about Brat. My parents are 80 years old. Now, it may be because I have a Charli xcx tattoo, but they know Brat is Charli xcx.

When you do a really strong branding like that and you're at the Democratic National Convention, I tell this story that a 70-something-year-old senator from Hawaii, Maisie Hirono, comes up to me, looks me down in the eye and goes, I'm brat. And I'm like, what the fuck world do I live in right now? But the thing is, is like, that is that branding that did that.

WD: Right.

JC: So did she need it? No, but most of the time what you do, since you are not using strong enough branding and creating strong enough conversations, you need to be reinforcing. This is what this looks like. There's one of the reasons that, if you look at all the groups, there's two [publications] that show the most merchandisable brands every year. They all have one thing in common. Every one of them never changes their logo. So it's Kiss, Metallica, Misfits. It's always the same ones that are the ones that stay for a decade in the top 20.

Taylor Swift, you could argue very much that, yes, she's changed some things. But in recent times, if you look at the trend of her merch, she was in a very similar font. The fact is every bit of graphic design is an emotion. And you want to be having an emotion that aligns with your brand that you're reinforcing over and over again to people.

Because also it sells what people buy merchandise for and what album covers are for too. It's this virtue signal that: I am part of the subculture. You see me alone in a bus station. You're bored waiting four hours for the bus. We both just mixed, maybe you're gonna talk to me because you see I'm wearing a charli xcx piece of merch.

WD: And I guess in one sense, part of me is thinking, okay, well if you do album covers that are just a photograph, right, and it has no text, I guess you have the chance to put the logo on the crinkle outside of the physical, but you’re losing that opportunity a little bit to have the logo.

JC: Yeah. I think there's also just synergistic ways to put it in. You could argue if you're Axl Rose and you're doing Use Your Illusion or something... where you know you want this expensive piece of art that you paid for that means a lot to your message or whatever that sure you can make exceptions, but most people are not doing this. They're not even putting their logos in the AI junk that they got for free right on midjourney and it's one, I think a lot of time a lack of thought and two, I think a lot of lack of best practices and foresights of what this all does.

WD: Because you were saying in the 90s that kind of fell apart a little bit, the vinyls, and I’m thinking of Aphex Twin as a kind of great example. He just he just pushed [the logo in] almost an ironic way. I don't know. I wasn't really into it. Or alive [then].

JC: Well, here's the thing. Both alive, a fan, and another tattoo I plan on getting, what was interesting with Aphex Twin… they mistake this thing in mystery in artists. A lot of the time the thing of mystery is a person who doesn't do a lot of interviews. [He didn’t give many interviews.] But what did he do? He did the most heavy branding of all time.

He had a logo and what were most of his music videos? He'd take his fucked up looking face, put it on the album covers, the music videos. He'd put it on children. He'd put it on dancing girls. And he was always branding because he was like, yeah, I look fucked up. He's like, I'm an ugly motherfucker, but he kept branding that too and putting [it] up on everything. And the other thing is, is much like Brat is, it's a total alignment. Compared to whatever else that everyone else in that genre would always do… these minimalist art pieces. And then what was he doing? Bad drawings of his face, way too overexposed pictures of his face, right? Just these things that set him apart from everyone else in his genre, which is what good positioning does as an artist that sets you apart and gets a conversation created about you.

WD: What you're saying is making me also think about is the decisions that you're making in terms of, do I put the logo? Do I not put the text? You want to balance being easily recognizable, but then having people to do a little digging to find the lore. You know what I'm saying?

JC: Asking someone else how they feel about it is often the thing I see. So a good example is like when you see even Kanye satirizing a Metallica thing, what did that make you feel? That he took their culture? The discussion of that Kanye was the first black artist to largely take from white culture to start conversations, whether it's working with Daft Punk, John Bryan, whoever, you know, you see that same thing, Metallica obviously being as white as it gets. You create another conversation.

So I just did this thing. I did the largest music listening consumption survey of the year.

WD: I participated in it.

JC: Amazing. I appreciate it. So one of the things we saw is the top two ways people still discover new music, according to the survey, is word of mouth. Number one, being word of mouth in person. Number two, being word of mouth online. Trusted friends telling you what to do.

So to your point, what is that? It's the discussion of what this artist just did. A lot of times the word of mouth is did you create a conversation from that piece?

Another piece of shitty AI art? Not so much. A very well thought out image that says something about the artist or gives an emotion? Often great. So I think ultimately that's probably the more important thing, rather than if something is going in this direction of having less text, more text, whatever. It's more just the balance of expressing the artists and their intent. Who they are and then doing something that's a bit different or that's kind of an event.

An event is a word I like to use. One of the big things, I think, is often a contradiction. So I have this saying, the contradictions are the conversation. For example, Charli's Brat contradiction was that if you looked at every other pop girl who put out an album in the last few years, you can't show me one that they didn't put themselves on the album cover, usually with their ass prominent in the photo, Billie Eilish being an exception to the ass. But, like, that's usually what it is.

But shitty, abrasive, green with a faded font is the polar opposite of that.

WD: Right.

JC: If you listen to her Zane Lowe interview, she fought for that because she knew that that was the position she wanted to take is, I don't got to play this fucking game. I'm above all of you.

That is often what the game is, is you're saying I'm above all you. Sabrina Carpenter's whole message is, I'm more expensive than all of you bitches. You know, each one has their own position. What are you serving with a contradiction that contradicts either people around you or something within yourself that you're saying: this is different. Charli's even saying this is different than my previous work. On Crash, I'm in a bathing suit, but I'm also bloodied, because I don't care about being as polished as Taylor Swift. I could show myself with my face smashed and not care.

WD: I’m curious what you think, but it may be that for an artist at her level, trying to get to that next stage, [doing the art in that way] really mattered. But for people who are just starting out, who are trying to get into the grind of reels or that kind of thing, how do you think [album] art plays into that?

JC: One of the most controversial TikToks and reels I've ever put up was when I said album art is the least important place to put your budget when you don't have one.

One, it very rarely affects somebody's decision about whether they're going to click it because most of the time when they're presented with music, it is smaller than your pinky nail. You can't really see it, so you have no idea what they're signifying in the first place, if it's even present, which it often isn't on playlists depending on the app.

WD: Well, that's the other thing that I was thinking, what are they… canvases? Actually, this happened to me the other day, which honestly, as someone who likes album art, it's a little frustrating…

JC: Same, same.

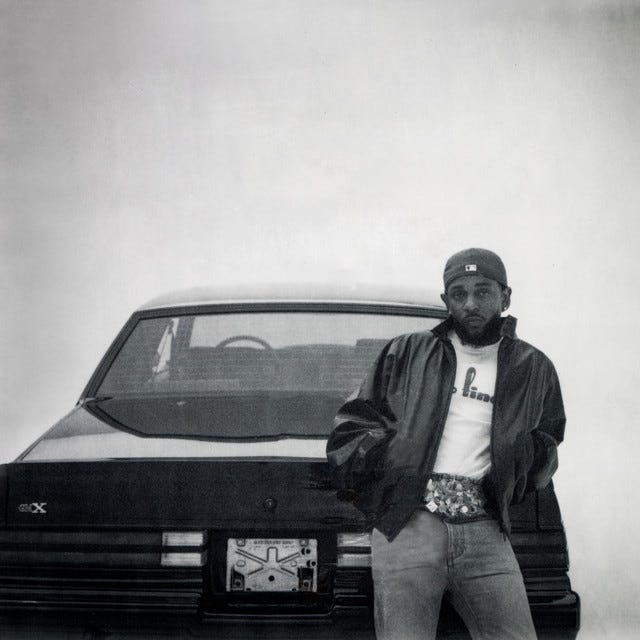

WD: You might find this funny, but I noticed the album art for the new Kendrick Lamar album. I found it funny that Jack Antonoff worked on the record and I noticed that his record was also a black and white cover standing in front of a car. And then also The 1975 record was black and white and had a car, which I was like, this is funny, but I wanted to look at the record. And I was like, I can't look at the record cover close up because there's a canvas on every freaking song on it.

JC: I think when you're making all these YouTube thumbnails, you're creating so much art every single day, right? Artists create art constantly and so because of that you are almost in a fatigue, I think it's sometimes that you're having to do so much creative. And then with the canvases, canvases are interesting now that people are using the Spotify For You page feeds, in that you do need something eye-catching and culturally signifying.

Like when you're scrolling through a lot of people, then you go, oh, that looks striking. That sounds striking. If there's an emotional alignment with the two, you can often convert a listener a little better.

We've seen numbers. Spotify also pushes the artists to do canvases more. They basically made it mandatory at this point, basically to push you to have a canvas to your song.

WD: Which I think makes sense with what you're saying with that controversial reel, because if [album art is] not going to, in the grand scheme of things, be converting listeners or holding that much weight in how people are seeing you, then why are you putting this much time and money into it?

JC: Yeah, and that's kind of my thing. What I was saying in that reel, and obviously there's always context collapse when you're doing short form compared to the things that you've said in long form, because you can contextualize more. But when you're telling me I have $2,000, I can't advise that.

The album covers doesn't help your click through. What it helps is brand reinforcement, which you may not have the money for, right?

WD: Yeah so maybe people should just create one logo and then just cycle out colors. *laughs*

JC: To be honest with you, one of the things I would advise is take your pose if you're a person who wants a picture of you and then remove background. Keep swapping through colors that are in the brand. Or start changing filters. Learn some wild effects with color correction.

A master class on early imagery. They even had multiple creative directors in the group but like Brockhampton when there was only 3,000 of them. What were they doing in the Saturation era? They were saturating a bunch of images that they would then use in other ways. It was like “saturation” was also that they were going to saturate the market with a massive amount of music, but they also extended that to the brand of let's just take the same photo and saturate it in a different way.

WD: Which was also genius for those covers for all the albums, because they could just put a different guy on the cover.

JC: Different guy on the cover, different title card on each video. Just very simple, small tweaks that were not hard to make.

WD: Something that I always hear you talk about is YouTube is still huge for Discovery.

JC: I mean, I’d argue bigger than ever.

WD: Yeah. Because I definitely remember [Brockhampton] being a big band that blew up on YouTube.

JC: 100%. You can take two polls of how YouTube did it. One, they showed up so much to YouTube. They made lots of more important content. But three, Fantano. And Fantano is a creature of YouTube.

So YouTube changed their algorithm about four or five months ago to surfacing smaller artists' music again on the browse page.

WD: It’s great.

JC: Yeah, and it's an unbelievable change I see in artist. I get like a video from a band that has 3,000 views on the thing that came out 14 days ago and it's like well clearly [YouTube] sees this is for me I hit play. And I may like it, I may not.

WD: What do you think are some of the mistakes, besides just not being your thing? If the algorithm is feeding you something, is that even something that you can help, or have you already done everything you can by the point where an algorithm is feeding you to someone?

JC: So there’s a two-fold problem. One, I am paid to listen to so much music it’s impossible for an algorithm to understand me unless I went and did that on a separate account. I actually do. I keep a separate TikTok account to look at when I don’t want my algorithm fucked up. I used to do it with Spotify.

But the big thing I really see is that, you can align yourself and make a better algorithm. So if you think about it this way, a group I think about a lot who I work with and are my friends is a group called Health. Health basically build the algorithm they want by collaborating with other artists. Now, not everybody's as fortunate as them to have all these other artists be like, of course we'll work with you, reaching out to Lamb of God or 100Gecs and them be like, hell yeah. But the point being, you can do lots of intentional things to build the algorithm.

You can't get connected to Drake when you have 40 monthly listeners, but you can get connected to a smaller artist Drake's fans like and keep building up from there and from there and just keep going up the thing by just doing a lot of smart practices.

WD: Not that you can trick the algorithm necessarily, but if it’s giving you the same type of stuff, how are you going to stand out in that way, if you’re just given a version of something you’ve already listened to? I think sometimes you could have a better chance if it was something you’ve never heard before.

JC: Artists will come and be like, I don't really sound like anybody. I'm like... A gift and a curse. It's going to be the hardest to get your first fans. It's going to be the easiest for you to grow.

People don't need a shitty version of Blink 182. You hit a certain point where you hit a certain amount of people who will listen to a shitty version of Blink 182. They just want real Blink 22.

When you're doing something unique with a unique set of emotions, there's a lot of potential there as long as the emotion is powerful. So you can create that, but you're right in the sense that I think people think a little too much that people's tastes are really narrow, when I don't think they're very narrow these days. In the average music listener, we see such a greater display of a vast interest of music than we ever have before.

WD: People are becoming more genre-less types of fans.

JC: While they may like discussing genre, they still are very fluid in all the things they will listen to and I think have a wider palette than we've ever seen before.

WD: I don’t know if we quite answered all that, but when I was talking about if someone’s getting to your algorithm, what are the worst mistakes that people are making once they get there?

JC: So a lack of emotional alignment is a very big one. What I mean by this is, somebody will go, you know, we're in a coffee shop right now. I always want to film a video in a coffee shop and then they're a black metal band. That doesn't align emotionally.

Now the contradiction can be hilarious. It would be really hilarious to have the black metal band playing at the coffee shop while everybody's trying to be peaceful and chill. But what I think most of the time I see that goes wrong is it's just like, I have an idea, I shoehorned it, and it has no emotional relevance to [the music or band].

One of the more interesting things I saw this year is Gigi Perez being one of the most viral artists of the year. It's like, girl makes sad girl music and she makes viral TikToks laying in her bed being depressed. It feels like the song because her music is about laying in bed being depressed. The emotional alignment is shocking how well it works.

Do you know there's this group called tsubi club?

WD: No.

JC: It's nuts. Two songs in two-ish, maybe three years. Both have millions of plays, but also the insanest music videos you'll ever see.

You look up tsubi club laced up. I have very rarely seen more conversation around an artist with two songs out being like, this is the craziest music video I've ever seen. But it also feels like the song, which is why it also works. Because the emotional alignment is really, really important.

I think people forget that, like getting back to album covers, whether it's TikToks right now, whether it's the album, whatever it's like when you're aligning and making an emotional world that actually other people are like, yeah that's what that feels like, it makes everything more powerful.

WD: For some of the readers or listeners of my newsletter who might be scoffing at, you know, these reels, or frustrations with making reels or whatever. What I’m hearing is it’s kind of the same thing as scoring a film. Where the thing works when the visual and the music are emotionally aligned. That’s when it’s working and that’s when it’s powerful.

JC: It's 100% that. I truly think a lot of the time when people are mad about these things, it's like, yes, I can understand if you're mad that you don't have the time to do it, stuff like that. But what I would also say is, are you familiar with the Magdalena Bay?

WD: Yes.

JC: So one of my favorite things about them is that everything they do is their art project. It's just this giant thing and there's even groups, we were talking about Thursday before we started recording. Thursday has always just been the band's art project in any way they're doing. They don't want to do a video if it's not part of the art project. They don't want to do album art or merch if it's not part of the art project. I think a lot of times musicians are not getting inspired by how do you make this an extension of your art project that you keep doing cool things that are within this artistic world.

I see the numbers. No one studies this more than me. A lot of the groups who are treating things like it's their art project are getting rewarded in a very big way.

WD: And by art project, are you saying that every piece, from the TikToks, and the things that people might be more careless about, they are all feeling part of the world of the band or group or whatever?

JC: They make a hat for a benefit. It still has to have a tie back to the world. I hate this world building term.

WD: Why is that?

JC: Because at best most of these people are barely building a cottage never mind a fucking world. It's the same way that when you're like “marvel cinematic universe,” It's fucking eight characters with barely any development. Fuck off. I don't want to hear universe.

I went to Virgil Abloh's museum exhibit. I don't want to hear the Virgil Abloh universe, but I saw it was a body of artwork. And there's nothing wrong with that.

And you can be diverse in your artwork. To be honest with you, I create lots of different things. I treat every one of my YouTube videos as a part of my art project.

I always go back to Phoebe Bridgers. Phoebe Bridgers treats it like an art project. She can also be real fucking silly on Twitter and on short form. She can take a topless photo on Instagram and laugh about it. She can fake kissing Matty Healy in front of her boyfriend, Bo Burnham, and make a post about it. But she's also creating her art project. She's filming the Boy Genius video at a monster truck rally, and that's part of her art of like, isn't it weird I'm in this situation? Your art can be whatever you see it as, and that world can be built whatever you see it as, but I think that that's why so many people don't enjoy doing this, is they think that they have to twerk on camera when they're not a twerk on camera type of person and that's not what it is.

WD: It’s funny because it’s making me think emotional alignment is just like a meme. It goes viral usually because it’s hitting someone’s emotions, whether it’s funny or fucked up or whatever it is.

JC: I think it’s either Brad Troemel or Joshua Citarella have that theory that a meme is just the most effective way of telling a story in a fast way. And yes, you may need to know some of the backstory to get it, but it still is the thing.

I always think back to Mac DeMarco years ago, hired a meme maker for his music. You can Google it on Pitchfork.

WD: That's very, very interesting. That's very genius of him.

JC: Yeah, but it really is the thing of that, at that time, the highest currency— we're often thinking of music marketing about ROI for your dollar— When I saw that, and I should say, you could waterboard my best friend's darkest secrets out of me by playing one Mac DeMarco song to get me to get it to stop. As a band, I have no interest in their music. I saw that, I was like, that's one of the most genius things, because it's the most effective marketing at the time.

WD: It reminds me of, I think I heard that Gracie Abrams’ team was hiring people to do fan accounts.

JC: This is the most common thing to do. In fact, the most interesting thing we see right now is that artists who don't post and kind of refuse to post, that's what their teams are doing to compensate for them.

I'm going to not say I know this for a fact, but I'm going to say I heard it from a reliable source that that is a lot of the Mk.gee strategy is because he won't make content, what they basically have is tons of accounts that are just posting anything he does. They get it out there.

WD: I mean, it's genius.

JC: It really is. And then the other genius thing is, you know this, that Shaboozy hired that firm to make fake fan fiction of him?

WD: No, I didn’t know that. It’s like manufacturing consent.

JC: Yeah, basically. It’s not far from it. There’s this term, do you know this term hyperstitions?

WD: No, I don’t.

JC: I highly recommend, I have a friend Brogan who goes by Art Chad on YouTube. He made a really good explainer on hyperstitions, but the hyperstition is the idea that you creates something that's not true.

So for example, “JD Vance having sex with a couch,” but it becomes so popular everybody believes it's real. No one could tell.

So Shaboozy hired this firm that said that he is Dolly Parton's godson. He is not Dolly Parton's godson, but they paid to create that myth online. They used a AI generation of Charlamagne tha God saying it on Breakfast Club as if it was true.

WD: Crazy.

JC: And that got it into the zeitgeist. It got a conversation. And what do we have from that? The longest-running number one song from an independent artist in 50 years.

I wouldn't say that's the sole reason. I think the main reason for its success is it's a very good song that people like yelling in bars very loud. And the contradiction. A large black man with dreadlocks singing a country song. Very big conversation. That’s a contradiction that creates a conversation.

Naomi Klein has this theory in her book, Doppelganger, that we’ve kind of hit a point where a lot of people would rather believe the most ridiculous version of the truth than the truth.

WD: Yeah.

JC: That is the logical conclusion, is that a bunch of bullshit and hyperstitions are going to spread.

But yeah, Gracie Abrams doing anything to spread her music, especially more legends and lore and things about who she’s dating. Well, her father is one of the greatest fiction producers of the last century.

WD: Makes a lot of sense. Does that kind of stuff excite you, creatively? Or does it scare you?

JC: So a lot of people don't know this, that I speak on, produce two of the most popular political podcasts in America. I used to, one of my other political podcasts was a podcast called Fever Dreams, where we chronicled the conspiracy theories and QAnon for two years. I see where bad things go.

There's a very good documentary that shows a lot of this HyperNormalisation by Adam Curtis. I have a line from him tattooed on my arm, “lost in a fake world.”

When people believe they're lost in a fake world, they don't believe anything. They lose motivation, they lose hope. They stop dreaming and a country goes to decline.

I usually condone by any means necessary promoting your music. I think this is fire that the world burns down with.

WD: So when you're advising and consulting, you're kind of trying to go different routes than that kind of manipulating? It’s hard to because you get pulled into it, just by the nature of [the internet].

JC: The place I like to be is leaning into what fans are saying about you. If it’s just fun and playful and playing with it a little, I think that could be kind of fun. Do I think making up outright lies where people no longer know what the truth is? I find that unethical personally. But that would be the line I personally draw, but it really is for the artists to do themselves.

WD: It’s interesting with the Shaboozey thing. I could see a little bit of annoyance at all the Nepo-babies. So his team’s like, why don’t we fuck them?

JC: Well, it's one of the biggest conversations. It's a very funny thing, when I talk to people about viral TikToks, the number one thing I have to say in their feedback, they're like, we're going to do this thing. I'm like, too smart. You got to be more dumb. People are fucking morons. What's the dumbest thing everybody can discuss? Your parents are rich. You got here without merit. It is the easiest thing in this culture to discuss right now. So when you're creating this conversation, that is the easiest thing to discuss. It's way more apt to go way more viral.

Whereas, if the conversation is a complex one about, is country music still scared of race? Well, it's a complex conversation. Beyonce not being the country music awards, strike against it. Shaboozey being on, but not as honored as he should for a song. is that harder conversation to have, with a lot more detail and a lot more knowledge.

Whereas you could just say, it's fucked up Dolly Parton's famous, he's Nepo-baby.

WD: [To] end on a more optimistic note maybe, any particular words about what’s exciting you?

JC: Every week of my member feed, I cover artists who went viral, going from no fans to a bunch of them. I look at the most viral song in America right now. It’s Sam Austin's “Seasons.” Dude was homeless in the last two years. Did not have much going for him 700 days ago. And now is getting 2 million streams a day on a song going viral. Has a great back catalog that's getting discovered too.

They uploaded through TuneCore. They're not on a major label. They were out for a little while. They were on Atlantic where I used to work. But right now that song went up through TuneCore. It went viral six months after it was out because TikTok liked doing fit pics to it.

Show me another time where we had that happening as often as it does as now in the history of music. The 1950s, some people could point to some songs like a “Louie Louie” that had success like that, but I'll remind everyone, 1952 was almost three quarters of a century ago. That's cool. That's a long time of lifetime since things have been this good for it.

The problem is we don't compensate very well for it. Musicians get paid worse than they've ever been paid.

WD: Oh yeah, totally.

JC: That's the thing we have to start doing, and the way we start doing that is we hope the Justice Department burns Live Nation to the ground, and we hope we can stick a fork in it the rest of the way after that, since Live Nation is the single greatest [reason], way more than Spotify or YouTube.

WD: Oh really?

JC: Look up Live Nation More Perfect Union on YouTube. Live Nation is the greatest reason that musicians are not making money on touring, which used to be a very big reason for the way musicians were funded. And then the second being that when music piracy happened, we were met with the lowest common denominator in negotiation because major labels were their most weak during negotiation points and since then major labels now are so weak by just lack of power.

There’s also Securities and Exchange Commission laws that make it so that the major labels can't bind together and “unionize” since they're corporations. The four governing parties (big major lables) can't negotiate against Spotify as a monolith, so they don't have more individual power and if they communicate with one another about the negotiations, that's a security and exchange violation.

What we have to do is we have to unionize and boycott, and then we can get a better world.

WD: Well, thanks so much. Kind of more optimistic…

JC: Yeah, I’m not really good at that.

Share this post